Well, whether or not the former British Prime Minister Harold Wilson was right when he declared that "a week in politics is a long time", a week (or two) in central banking certainly is. Who ever would have dared to say that this occupation seemed to be a boring and mundane one?

In fact, despite a growing sense of calm and order on the surface, the situation in financial markets following the recent Federal Reserve decision to

lower the discount rate can hardly be considered to have returned to normal. Yields on short term US treasury bills have moved up and down, but in general they are maintaining a form of orderly decline

as investors scrutinize Board minutes and continue to bet that the Federal Reserve will probably cut the benchmark federal funds rate at next month's policy meeting.

The German banking sector also

is also struggling to regain some kind of normality, while the Bank of Japan

has continued to inject liquidity into the Japanese banking system. Perhaps most visibly and evidently of all the Bank of Japan

maintained rates steady at the level of 0.5% in part at least due to concerns about the liquidity position in the global banking system.

Obviously this entire situation is leading to all sorts of speculation about the future direction of interest rate policy in all the major economies. Jean Claude Trichet continues to keep people guessing, but

it is now really rather unlikely that the ECB will proceed with a quarter point raise when it meets next month. Among other factors which will be up on the list of reasons for not raising will be the fact that

the German economy slowed notably in Q2 2007 (as

did the Italian one), while previous strong prospects like Spain and Ireland now look very vulnerable to any tightening in mortgage lending conditions. It also seems to be pretty much a foregone conclusion that the next move by the Federal Reserve will be down, and the only outstanding question really is when.

So when you stop and think about it, in monetary policy terms at least, rather a lot, not to say almost everything, seems to have changed over the holiday season, and the markets will now need time to assimilate the implications of all this.

Obviously we need to wait and see how the financial markets respond to the latest move from the Fed, but my feeling is that the so called "credit tightening" (or liquidity crunch) isn't over yet (and not by a long stretch), and that even were the "liquidity crunch" to come to an end soon the consequences for the real economy are going to be important, since credit - both corporate and private, and possibly even sovereign - will more than likely be harder to come by. What this "harder to come by" really means is that you will have to pay more for it, especially if your credit valuation is not of the highest (as was the case with the US sub-prime home purchasers).

But it is important to be clear here that what we have at this point is a liquidity crunch and not a generalized credit crunch, although evidently the danger is that the former spreads to the latter, which, of course, it may well do if the impact of the liquidity crunch on the real economy is seen as being sufficiently important as to warrant a good deal more caution in lending. It's as simple as that I think.

Basically liquidity crunches occur from time to time when asset prices decrease quickly, since banks typically demand more money and become more reluctant to lend out the money they already have. In order to maintain adequate liquidity (and guarantee its target refi rate) the ECB, for example, normally carries out a liquidity "top up" operation once a week. But what this means is that any sudden shifts in demand for and supply of funds which take place during the week in-between the "top-ups" can lead to liquidity squeezes. When banks sense there is not enough liquidity in the system then they start to hoard it and as a consequence liquidity can dry up very quickly. In such situations the ECB (or the Federal Reserve, or the Bank of Japan) may provide liquidity at a higher frequency than normal until demand and supply stabilise again and overnight rates once more return to their normal levels. This is the process we have seen at work over the last week or so.

Now this kind of liquidity crunch should not be confused with a more general credit crunch where credit conditions are tightened across the board vis-à-vis companies and consumers. At this point in the story there are no real signs that this is happening. In the eurozone, for example, M3 growth and broad credit growth are still at very high levels and lending standards are still generally favourable. The problem is that if the current financial crisis intensifies, and in particular, if there are perceived to be ongoing consequences for the real economy which derive from the liquidity crunch, then there is a genuine risk that we may see a broader tightening of credit.

In order to address this risk we need to think about why this liquidity crunch has happened now, and indeed about what it is that has been the immediate cause provoking it.

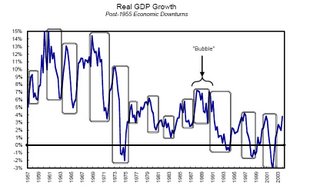

On the first count, the broad background has to be that the current cycle of economic expansion - which after all started back in 2001/2002 - is quite possibly nearing its peak. Volatility has been steadily creeping into the markets since the spring of 2006 - in Hungary, in Iceland, in Turkey - and often such events are early warning signals of bigger trouble coming further down the road, especially if the volatility increases. The US economy has been visibly slowing since the start of the year, the credit scare will not make it any easier to restart the critical housing sector, and

consumer confidence is evidently down on all the worries and fears being expressed. Indeed this concern is already indicated in the Fed statement about downside risk to the economy, which is evidently a departure from the earlier inflation vigilance tone. GDP

in Japan also slowed natably in Q2, as it did in some key Eurozone economies (most notably

Italy and

Germany).

This gradual "waning" of the present cycle has evidently been reflected in the financial markets and since the spring volatility in financial markets has been steadily and notably increasing in anticipation of the arrival of a bigger problem. That "bigger problem" it would seem is now with us.

Turning then to the immediate (or in the terminology of the Greek historian Thucydides the "efficient") cause of the crisis, it is important to allow ourselves to think about significance of the fact - as few commentators seem to have really done - that the whole issue started with sub-prime lending in the United States. This detail would seem to be important for three principal reasons. In the first place these mortgages were made to people in what you might consider to be a "high risk" group for lending, and obviously the risk was too high. This appreciation may well now lead the banks and other financial institutions to examine all the other "high risk" assets they have in their portfolios and to begin the process of systematically discarding them. This I do think will happen.

Secondly, it is not insignificant that the high risk group which set things in motion was associated with the property sector and this little detail will surely have implications (see below) which reach right across the real economy given the important role which construction and housing have been playing in the current cycle.

Thirdly it is important to notice that the sub-prime defaults problem surfaced in the United States, and that the Federal Reserve started the interest rate tightening cycle at least a year before most of the central banks in the other major economies did (with the significant exception of the Bank of England). So this means that the sub-prime population in those other economies (who of course have also been receiving money) have yet to start experiencing significant "distress" in the way their US counterparts have. But they will do. It is just that we are most probably still at 6 to 9 months distance from that stage elsewhere, and this is just another of the reasons why I think the problem will be a drawn-out affair, and any real economy slowdown may also have some duration attached to it.

Coming back to any possible general credit crunch, as I say, were this to occur it would undoubtedly make itself felt at all levels, since the banking sector has clearly had a big shock, and any credit tightening will clearly involve individuals, companies and even governments (and again it is interesting to note that the Fitch rating agency has already replied to some of the criticism

by downgrading Latvian government debt). Just how it may affect them is what we are now waiting to see. But it is important to bear in mind that such impacts on new and rollover credit would occur regardless of the extent to which central banks lower their base rates, since what will have happened is that the lending environment will have deteriorated, and this deterioration is likely to influence conditions in new lending (or rollover credit) for years rather than months into the future.

Obviously existing mortgage holders on variable rate mortgages can get some fresh air from any loosening in the base rates, but it is the demand for new mortgages, and activity in the construction sector, and not locally but globally, that we need to be thinking about here. Clearly construction growth can slow, as lenders become more choosy about who - and under what conditions - they lend to. This becomes important for the real economy when we come to consider the importance which construction activity shares have had in economic growth in some major economies - the US, the UK, Spain, Australia etc - since the turn of the century, and the impact which the so-called wealth effect has had on the rate of growth of private consumption in this self same economies. So clearly, in some developed economies, economic growth is now likely to be rather weaker, and for some time to come.

But any looming "credit crunch" is also likely to affect the so called "risk appetite" (that is the willingness to invest in riskier areas or activities) and the place where this is most likely to be felt is in the emerging market area. Those emerging markets which are considered to be most vulnerable will undoubtedly have the hardest time of it, and this brings us directly to Eastern Europe I think and to economies like those

in the Baltics (

Latvia,

Estonia and Lithuania),

to Hungary, and then maybe (if there were to be contagion) to the larger economies like Poland and Romania. Alarm driven reports about

the dangers of a hard landing in the Baltics have been floating around for some months now (I say alarm driven not because the danger isn't real, but because most of the reports are quite superficial, and don't really appreciate

the magnitude of the problem). Whatsmore, as the Bank for International Settlements pointed out

in the June edition of its quarterly review , in 2006 Eastern European economies accounted for a staggering 60% of new emerging market credit:

Emerging Europe overtook emerging Asia as the region to which BIS reporting banks extend the greatest share of credit. Since 2002, growth in claims on the region has consistently outpaced that vis-à-vis other regions. With a record quarterly inflow, emerging Europe received over 60% of new credit to emerging markets, bringing its share in the stock of emerging market claims to 34%. Less of the new credit went to the major borrowers (Russia, Turkey, Poland and Hungary) than to a number of smaller markets, notably Romania and Malta, as well as Ukraine, Cyprus, Bulgaria and the Baltic states.

To quote the Economist's Buttonwood, "WHEN investors get twitchy, developing countries are usually the first to pay the price.", and those who are most exposed get to pay a higher price than those who are less so, I might add.

Well investors are definitely twitchy right now, and, as

Danske Bank Senior Analyst Lars Christensen commented last Wednesday (pdf link), one piece of evidence that the markets are getting nervous about this whole problem set is the fact that signs of pressures on the Latvian currency (the lat, which is currently pegged to the euro) are now re-emerging after some months of calm. The

Hungarian Forint has also been coming under mounting pressure during the last couple of weeks.

At the end of the day though, and when we come to look at the actual mechanics of risk, I cannot do other than agree with the Economist when it describes the Baltics (and even Hungary for that matter) as being "financial pipsqueaks". The big issues are obviously going to come - if, that is they do come - in Poland and Romania, due to their size.

Whilst Hungary may in some ways be considered to be something of a special case, the general problem of the Eastern European EU10 can be simply summed up: they are experiencing rapid catch up growth which they are unable to live up to on the supply side due to severe labour shortages being produced by the impact of

both strong migration westwards across Europe (driven by the large wage differentials), and the sudden drop in fertility following the fall of the Berlin Wall back in 1989. The "missing children" who never arrived following the drop are now the "missing young people" who would be steadily arriving as young labour market entrants and facilitiating the much needed growth process. These problems, it should be noted, are now long term and structural, so there is no easy fix. As a result wages all over Eastern Europe (see

here for Romania), and

even in Russia (and

here), are

now starting to rise dramatically.

Claus Vistesen and I have been trying to get to grips with all of this (once we became aware of the Latvian situation) both theoretically (on

the Demography Matters blog, where you can find

a whole slew of recent posts) and practically in terms of

back-of-the-envelope calculations about

how soon the crunch will come, and where.

In principle I would say Poland should have two or three years to run before getting to where Latvia is now (although the Polish government are, it should be noted

busily out looking for labour in India right now), but, of course, and this is the whole point about what is happening now, and about why this downturn may be a little different from earlier ones, the financial markets may not let them get to two or three years from now as is. Once the financial markets wake up to the fact that Poland can ultimately get through to where Latvia is now, then there may well be fireworks8something similar can also happen to Romania, and both the IMF and the EU Commission have been pretty critical of the way the government is

running up the fiscal deficit there). Poland, it seems,

is going to have elections in the autumn so there will plenty of opportunity coming up for the markets to fret about the issue, should they get into the mood for fretting about things.

Danske Bank's Lars Christiansen had a research note last week which is of some interest for our assessment of the current situation (see

this post for an earlier research note of his which is also worth the time to read). Published under the header "

Emerging Markets: Looking for the safe haven" (watch out pdf), Christiansen accepts that what we have is already a global credit crunch, and takes the view that this crunch is now spreading to Emerging Markets (EM), with many of the high-risk EM currencies (the Turkish Lira, the Hungarian Forint, the Polish Zloty, etc) now coming under constant fire and attack. In this situation he allows himself to ask the question as to what countries may be most at risk, and answers in the following fashion:

In a situation where liquidity is tightening there is no doubt that the most liquidity-“hungry” countries are those with large current account deficits and large external debt. In this category we find Turkey, South Africa, Hungary, and Iceland. Furthermore, risks are heightened in the Baltic states, Romania, and Bulgaria.

That would seem to put Eastern Europe pretty generally on the map I would have thought. Chrisiansen seems to accept the arrival of the credit crunch as now a fact:

For the last couple of weeks, we have warned that the global credit crunch could spread to Emerging Markets. This has now clearly happened, but given the major moves in the global credit and equity markets there clearly is potential for even more contagion to Emerging Markets. Therefore, there is also reason to start looking for safe havens within Emerging Markets. Here external funding needs will be the key.

Furthermore:

The credit crunch has triggered a strengthening of the yen and to a lesser extent, the Swiss franc. We would in particular watch the Swiss franc as many households in Central and Eastern Europe have funded their property investments with Swiss franc loans. Hence, if the Swiss franc strengthens further then it could put additional pressures on the CEE markets mostly exposed tothe Swiss franc.

This is really code language for speaking about Hungary (although there may be more) since in Hungary around 80% of the mortgages which have been taken out in recent times have been Swiss Franc denominated (via Austrian banks I should mention, so the Austrian banking sector is also partially at risk, although the Austrian Central Bank think they can withstand any potential shock

if you look at the "Stress Testing the Exposure of Austrian Banks in Central and Eastern Europe" paper presented here).

So here are Danske Bank's recommendations. The countries you are told to avoid are in red:

One bright spot - or potential safe haven - does exist in Eastern Europe however: the Czech Republic:

Finally it should be noted that the Czech koruna (CZK) – unlike most other CEE currencies – should be expected to strengthen in the present environment due to unwinding of CZK-funded carry trades. That said, the CZK is fundamentally not undervalued and the Czech central bank should be expected to keep interest rates below the ECB rate – especially if the CZK strengthening accelerates. That will limit the potential for strengthening of the CZK.

In case any of you notice some inconsistency in this view of the Czech Republic, since of course Czechia is also one of the "reds" (though to a much lesser extent than some of the others), I think it needs to be pointed out that other factors beyond the CA deficit need to be taken into account when evaluating the situation (the value content of exports would be one of these, what the deficit is based on would be another - ie are you importing machinery and equipment which can subsequently be used for exports - and the

openness of the labour market to immigration would be another - there is of course an acute labour shortage in the

Czechia , but they are

they are actively attempting to address this and they are even

out trying to recruit in Vietnam). Essentially the Czech economy seems to be on pretty solid ground (as may also be the Slovenian one), and you do need islands of tranquility in Oceans of tempest. So some countries will for this very reason prove to be win-win, while others may well, by the same token, prove to be lose-lose. Unfortunately historic reality is seldom just.

In conclusion I have to say that I would also be much more cautious than Christiansen is about Russia, since the political instability there is evident, as are the growing labour shortages, and internal tensions which these are producing. At the end of the day I think we need to see what happens next to oil and other commodity prices before we stick our necks out too far on Russia.

The employed population in this age group is fluctuating. It seems to have touched bottom in January/February 2007, and to be now increasing again. Given that the economy is slowing considerably while this employment expansion is taking place, one prima facie conclusion would be that productivity is not rising, and may well be slowing, since with more people working and more productivity the economy should accelerate, not slow. Of course one other possibility is that the average number of hours worked per capita is reducing - no overtime etc - and this is a possibility I will try and explore.

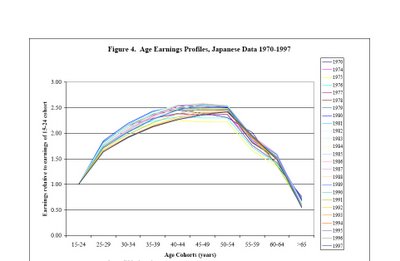

The employed population in this age group is fluctuating. It seems to have touched bottom in January/February 2007, and to be now increasing again. Given that the economy is slowing considerably while this employment expansion is taking place, one prima facie conclusion would be that productivity is not rising, and may well be slowing, since with more people working and more productivity the economy should accelerate, not slow. Of course one other possibility is that the average number of hours worked per capita is reducing - no overtime etc - and this is a possibility I will try and explore. When it comes to the age composition of the labour force we can also notice something interesting. Obviously the majority of the workforce are - at this point in time - in the productive age groups between 25 and 55. But it is also interesting to look at participation rates in the groups outside this age bracket, to see what is happening, and what the future has in stor. Below I have made a chart showing the numbers of people in the 65-74, 60-64 and 15-24 age groups. Now what is clear is that these two latter groups are expanding - this is what an ageing workforce means - while the latter, youngest group, is contracting.

When it comes to the age composition of the labour force we can also notice something interesting. Obviously the majority of the workforce are - at this point in time - in the productive age groups between 25 and 55. But it is also interesting to look at participation rates in the groups outside this age bracket, to see what is happening, and what the future has in stor. Below I have made a chart showing the numbers of people in the 65-74, 60-64 and 15-24 age groups. Now what is clear is that these two latter groups are expanding - this is what an ageing workforce means - while the latter, youngest group, is contracting. This contraction in the 15 to 24 age group can be for a number of reasons. In the first place it is simply a reflection of the fact that there are progressively less and less people in this age group, as can be seen in the next graph.

This contraction in the 15 to 24 age group can be for a number of reasons. In the first place it is simply a reflection of the fact that there are progressively less and less people in this age group, as can be seen in the next graph.