The highly open Czech economy is set to slow down considerably, affected by the deteriorating outlook for its main trading partners. Although GDP growth was still solid in Q3 2008, both exports and imports growth slowed significantly. The global crisis is expected to adversely impact the real economy particularly from the fourth quarter of 2008. Overall, GDP is expected to have grown by 4.2% in 2008 with a strong contribution from the external balance.

EU Commission Forecast January 2009

Analysts and followers of the Czech economy are basically agreed on two things at the moment: that the Czech is slowing (and rapidly), and that the dependence on car exports is a real achilles heal at a time when a generalised credit crunch means that the financing which is needed for people to make car purchases often quite simply isn't there. Beyond this point opinions differ. Some expect the slowdown to end in nothing more than a year of sub par growth, with a bounce-back recovery in H2 2009 (this is the view, for example, of Pasquale Diana at Morgan Stanley). Others take a more pessimistic view - like Danskebank's Lars Christensen - and fear that not only may we see a substantial slowdown (bordering possibly on outright contraction) throughout the whole of 2009. but also that strong deflationary forces are at work, forces which may well lead the Czech National Bank to become one of the first European central banks (hand in hand possibly with the BoE) to get into the tricky area of trying to operate monetary policy near the zero bound. Personally, after a long hard stare at the detailed macro data, I am in the latter camp, and to answer the question I pose in the title of this post, I think the Czech economy is very near to its first quarter of contraction, indeed we may even have seen contraction in Q4 2008. If we didn't it will be a very close call, since the not only has the trade impact been negative, and industrial output dropped like a stone, but domestic consumer demand - as reflected in retail sales - also seems to have been falling.

And the outlook for domestic demand certainly does not look any too positive, if the most recent consumer confidence readings are anything to go by, since these have been falling strongly since the summer, and surely suggest strong weakness in household consumption right across the first half of 2009, at the very least.

Industrial Output Falls Like A Stone

Czech industrial production fell in November at the fastest rate since at least 2000, dropping by 17.4 percent year on year, following a decline of 7.6 percent in October.

This fall is very substantial and it is clear that the Czech authorities urgently need to revise their growth forecasts in the light of this and other recent data, indeed some analysts - Radomir Jac at Generali PPF Asset Management in Prague , for example - are already arguing the drop may well mean the economy already started to contract in the fourth quarter. Others are more cautious. Still, one thing is common across all the analyses, we are talking about cars, cars, and ever less cars.

The collapse in activity across the region in 4Q08 looks truly extraordinary, and was correctly flagged by the PMI surveys, which sank to all-time lows. Trade data and industrial output and, to a lesser extent, retail sales all show a significant loss of momentum towards year-end. Much of this is due to weaker external demand, in particular in the auto sector, which is the region’s most important export. Car sales in the EU have weakened further, and several carmakers have announced a cut in their production plans for 2009. In the Czech Republic, Hyundai said that it plans to move to a four-day workweek and pay workers 70% of their salaries for a period of 1-3 months; Skoda also downgraded its production plans massively for 2009 (from 700k cars to 570k).

Pasquale Diana, Morgan Stanley

The Czech Republic has arguably the most stable economy in central Europe, but at a time when the world is being buffeted by financial crisis, there is no chance it will escape being hit next year. First in the line of fire will be the automotive sector which, with almost 1m cars manufactured this year, is responsible for about 10 per cent of the economy. Almost all are exported to western Europe, where new car sales have plunged in the final months of the year.

Jan Cienski, Financial Times

And the situation is almost sure to get worse, since the Czech Purchasing Managers' Index fell to 32.7 in December, from 37.8 in November, which indicates a very substantial fall in industrial output again in December.

Thus we can expect Q4 industrial output to be a strongly negative factor, and indeed this only marks a steepening of a trend we have been seeing since Q1 2008, if we look at the quarterly chart for movements in manufacturing output below.

Thus we can expect Q4 industrial output to be a strongly negative factor, and indeed this only marks a steepening of a trend we have been seeing since Q1 2008, if we look at the quarterly chart for movements in manufacturing output below.

Exports Fall And The Trade Balance Deteriorates

The fall in industrial output is basically a reflection of the ongoing deterioration in the CR's performance in external trade, and the drop indemand for exports. The monthly goods trade deficit was CZK 474 million in November, down from the very large CZK3.95 billion deficit registerd in October, but well below the CZK 12 billion surplus clocked up in November 2007.

Exports were down 18% year-on-year in the month compared with a 10.7% fall in October. The statistics office report said the decline in exports was the highest in the entire history of the Czech Republic. Imports declined 13.2% compared with a 5.9% drop in October. Total imports slipped to CZK 195.2 billion from CZK 221.4 billion.

Retail Sales Also Head South

In November, seasonally adjusted retail sales in retail trade (excluding cars) decreased by 0.3% month-on-month (at constant prices) and fell by 0.7%, year-on-year. As far as the automotive sector goes, seasonally adjusted sales were 3.4% down, m-o-m, and 5.1%. Sales were also down 0.7% month on month in October.

Koruna Continues To Fall

With all this negative data it is hardly surprising that the Czech koruna has been weaking significantly of late, and it depreciated again last week, losing as much as 1 percent on Friday alone (hitting 28.255 against the euro at one point, the weakest since July 2007) and 2.1 percent on the week.

Consumer Prices Already Falling

Consumer prices in the Czech Republic were down again in December, and fell by 0.3% when compared with November. Year-on-year consumer prices were up by 3.6 % in December (down from 4.4 % in November), while the whole year average was 6.3 % in 2008.

As is to be expected the month-on-month drop in consumer prices was lead by the fall in automotive fuel - 95 octane petrol hit its lowest level since March 2002, while food and non-alcoholic beverages were mainly down, with pronounced falls in the prices of flour, milk, butter, citrus fruit and sugar (by 6.7 %, 1.7 %, 2.7 %, 8.6 % and 1.9 %, respectively). But prices drop were far more general, and in the health sector, for example, medical products dropped by 0.5 %. Prices of goods in general decreased by 0.5 %, while prices of services increased by 0.1 %.

But what is perhaps more interesting is the way in which the "core" EU HICP index (ie excluding food, alchohol, tobacco and energy) has now been falling since August, and I do not expect to see an increase in this index in 2009, which means we should see negative core inflation in the CR in 2009.

But what is perhaps more interesting is the way in which the "core" EU HICP index (ie excluding food, alchohol, tobacco and energy) has now been falling since August, and I do not expect to see an increase in this index in 2009, which means we should see negative core inflation in the CR in 2009.

Industrial producer prices are also falling, and were down by an annual 1.5% in November. The most significant price decreases were observed in ‘coke, refined petroleum products’ (-19.0%), ‘basic metals, fabricated metal products’ (-2.1%) and ‘chemicals, chemical products and man-made fibres’ (-3.8%). Prices of ‘food products, beverages and tobacco’ fell by 0.5%. The big issue now is what will happen to inflation expectations? The strongest defence against the arrival of deflation is the expectation of inflation to come. To date these expectations have held up, but they could well turn negative at some point, and if this were to occur it would have a very significant impact on consumer behaviour (since evidently it is more interesting to delay that whimsical purchase till tomorrow, when the thing will be cheaper). If expectations do turn significantly negative, then it could turn out to be very hard work indeed getting them back into positive territory. Which is why I suspect the CNB will be pretty proactive, possibly more proactive than many are anticipating.

The big issue now is what will happen to inflation expectations? The strongest defence against the arrival of deflation is the expectation of inflation to come. To date these expectations have held up, but they could well turn negative at some point, and if this were to occur it would have a very significant impact on consumer behaviour (since evidently it is more interesting to delay that whimsical purchase till tomorrow, when the thing will be cheaper). If expectations do turn significantly negative, then it could turn out to be very hard work indeed getting them back into positive territory. Which is why I suspect the CNB will be pretty proactive, possibly more proactive than many are anticipating.

Moving Towards The Zero Bound At The CNB?

The Czech National Bank, whose next policy-setting meeting is scheduled for 5 February, have been cutting their benchmark borrowing rate pretty aggresively since last October, taking it down to 2.25 percent at its last meeting in December.

The drop of industrial output is “really considerable,” central bank board member Robert Holman said on Patria.cz. The bank’s “pessimistic” forecast scenario is starting to be fulfilled, he said.

The latest central bank forecast cut the outlook for 2009 economic growth to 2.9 percent, although the bank had an alternative (pessimistic) scenario which foresaw growth of 0.5 percent this year.

Today’s industrial production numbers and the outlook for inflation to drop to just above 1% in January should make the Czech central bank (CNB) even more dovish. We now expect a cut of at least 75bp at the next CNB board meeting in February. Furthermore, we would not rule out that CNB could be the first European central bank (maybe with the Bank of England) to go to (near) zero per cent interest rates. Therefore, we also recommend buying EUR/CZK at current levels.

Lars Christensen and Stanislava Pravdova, Danskebank

So far, January’s economic data published support our view that the CNB’s Bank Board Members are ready to continue easing, following the 150bp cut in policy rates in 2H08 to 2.25%. However, yesterday’s data have led us to review our previous forecast of a 50bp cut in the CNB’s policy rates, and we now believe a 75-100bp cut is likely to be discussed at the February meeting. Furthermore, we do not exclude the possibility that the CNB’s main policy rate could breach its all-time low (which was 1.75% in 2Q-3Q05) in February.

Jaromir Sindel, CitiGroup Global Markets

I am with Lars Christensen and Jaromir Sindel here, I think the CNB will move, and move pretty decisively to try to block the path to looming price deflation, and I guess a 75 bp cut (and possibly more) is looking very probable, with further cuts following inswift succession. Evidently the key piece of data will be the January manufacturing PMI, and in the short term I expect the PMI and not the actual output data (which obviously come later) to be dictating policy decisions. The statist office releases simply serve to calibrate the PMIs (post hoc) in this type of situation.

So What Is The Outlook For Czech GDP Growth in 2009?

Well, in trying to determine the future path of Czech GDP, the first thing we need to bear in mind - looking at the GDP chart above - is that the economy has been losing momentum since late 2006, that is the "stellar" catch-up growth component has been waning, and for some time. The second thing we need to bear in mind is that this is not necessarily a bad thing, since it means that the CR's economy (unlike many others across the CEE) is certainly not on a boom bust cycle. The slowdown in quarter on quarter growth is also evident in the chart below. In fact in Q3 2008, Czech GDP grew by 1.0% in comparison to Q2 2008 and by 4.7% in comparison to Q3 2007.

Well, in trying to determine the future path of Czech GDP, the first thing we need to bear in mind - looking at the GDP chart above - is that the economy has been losing momentum since late 2006, that is the "stellar" catch-up growth component has been waning, and for some time. The second thing we need to bear in mind is that this is not necessarily a bad thing, since it means that the CR's economy (unlike many others across the CEE) is certainly not on a boom bust cycle. The slowdown in quarter on quarter growth is also evident in the chart below. In fact in Q3 2008, Czech GDP grew by 1.0% in comparison to Q2 2008 and by 4.7% in comparison to Q3 2007.

What is interesting is that the weaker growth we can see in the chart has been largely a by-product of slowing private consumption growth (see my earlier post here, and this one here), which leaves us with the possibility that the Czech Republic economy - following along the path already charted by Germany, Japan, Italy and Hungary - may now be in the process of becoming an export dependent one. (Perhaps it sounds strange to talk about Italy as export dependent given its very weak growth, but this weak growth is in fact the outcome of continuing very poor export performance, since domestic demand has now been weak for more years than I personally care to remember). In fact final domestic consumption was still up by 2.7% in Q3 2008, and represented a contribution of 1.9 p.p. to GDP growth. Final consumption was particularly influenced by a year on year increase in household expenditure by 2.5% , while government expenditure grew by 3.7%. Fiscal stimulus should hold the government component steady, but I would expect the household one to drop back, and especially as we start to see job losses from the industrial contraction.

Gross capital formation was down by 2.0% on Q3 2007 and had a negative impact of 0.5 p.p. on GDP growth, although gross fixed capital formation taken alone was up by 4.5% y-o-y; in fact investment in transport equipment and in machinery and equipment was the main source of GFCF growth.

As in earlier quarters, external trade in goods and services was the main source of economic growth in Q3 and contributed by 2.8 p.p. to the GDP increase, despite a considerable fall in y-o-y growth rate of exports (from 13.9% in Q2 to 5.0% in Q3). This was the result of the marked fall in import growth (from 9.7% to 1.6%), hence external trade remained the principal source of GDP growth.

Reflecting Citi’s expectations of a recession in the eurozone, we forecast the trade surplus (both of goods and services) to shrink significantly in 2009 from its surplus of CZK108 billion in 2008 (our estimate).Falling commodity prices are likely to have been behind the improvement in the terms of trade in November, which fell in October. We believe this development has the following implications: the improvement in the terms of trade is likely to cause the foreign trade’s first negative contribution to GDP growth after three and half years, and GDP growth is likely to fall quickly to the levels of real gross domestic income, which was 2% YoY in 3Q08 and much lower than that of GDP growth of 4.3%.

Jaromir Sindel, CitiGroup Global Markets

Employment May Weaken

Employment growth, which has been one of the hallmark features of the Czech expansion, continued to grow in the third quarter and was up by 0.4% q-o-q and 1.9% y-o-y. Labour productivity measured by gross value added per employed person was also up (by 2.3% y-o-y). There were 5.327 million Czechs in employment in Q3 2008, 98,000 more than in Q3 2007. However, there is now some evidence that this favourable situation may now be changing.

Certainly, if we look at the chart below, the substantial drop in unemployment in the CR since 2005 is very impressive, and indeed even though the seasonally adjusted EU harmonised rate ticked up from 4.4% in October to 4.5% in November (the last month for which Eurostat have released data) the change is hardly a dramatic one.

However, if we look at the data from the CR's owb labour office, we find a reasonably sharp increase from November to December (unemployment was up by 32,000, compared with a 7,000 rise in December 2007), and if we look at the situation vis a vis vacancies (see chart below), then it is clear that the deterioration in manufacturing conditions is now affecting the labour market, since the number of vacancies advertised has now fallen from the April 2008 peak of 152,300 to December's low of 91,200 (the lowest number in over 2 years, which is all I have data for).

CA Deficit To Deteriorate, While Fiscal Spending May Increase As The Slowdown Accelerates

The CR does run a current account deficit, but it is actually a fairly moderate one in a regional context, although it is liable to increase in 2009. November’s narrower current account deficit reflects the slightly improved trade balance over October and lower dividend outflows from FDI, which dropped to CZK3.5 billion from October’s CZK12.3 billion. The current account financing requirement has been low but the deficit may have reached 2.8% of GDP in 2008 (up from 1.8% in 2007, and above the IMF estimate of 2.2% GDP).

The EU Commission forecast thatgeneral government deficit will be 1.2% of GDP in 2008. This reflects a much-lower than- expected deficit of 1% of GDP in 2007 and the positive fiscal impact of a variety of revenue and expenditure measures. For 2009, they expect the general government deficit to widen somewhat given the pressure on revenues and expenditure which will result from falling activity, rising unemployment and probable fiscal stimulus measures. Overall, they suggest that the general government deficit will widen to 2.5% of GDP in 2009 but should fall back to 2.3% in 2010 - although this surely reflects their benign slowdown scenario whereby a recivery is expected to arrive in H2 2009. The debt-to-GDP ratio is forecast to rise to above 30% in 2010, from 29.4% in 2008.

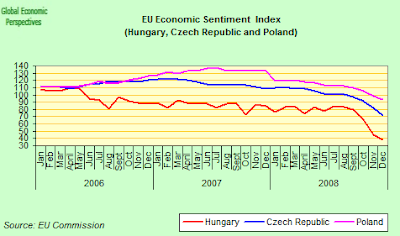

Conclusion: Central Europe Is All Recession Bound

This is basically the third in a series of posts, where I have looked at the short term outlook for three key central European economies: Poland (here), Hungary (here) and the CR, and the conclusion is that they are all headed into or near to the contraction zone in 2009. Cetainly Hungary is the worst case scenario, and Poland is struggling with a complex set of forex issues, but even the Czech Republic can not expect to escape unscathed.

Previously, as can be see in this chart for the EU Economic Sentiment index, Poland had been faring rather better its Central European neighbours. But the downward movement in Poland is now evident and pronounced, and in fact the contraction may ultimately be sharper than in the CR.

In their January forecast the EU Commission estimated that GDP growth in the Czech Republic would come in at 1.7% in 2009 and then edge up again to 2.3% in 2010. This now seems very much on the high side to me. I expect Czech GDP to be more or less stationary in 2009, with some downside risk to this estimate given the general problem of economic stability in the region and the very serious contraction which is like to take place in the German economy on which the CR is so dependent. I do not expect a resurgence in domestic demand, and the economy will now more than likely become even more export dependent, which leaves us with the omnipresent question, "exports to where"? On the other hand, at the present time we do are not looking at a "boom-bust" scenario, and the CR economy should fare substantially better than many of those around it.